The idea for this article changed over time. Initially it was supposed to be a short info about new game designed by Volko and to be published from PHALANX. Gradually, it evolved towards something like interview, grew in its size and now is released just when the Gamefound campaign for this game is about to launch. Still, I believe you are getting a decent amount of information about this new title and Volko is very scrupulous in explaining some of the design decisions. Hope you will enjoy it! And if you would like to immediately check the Gamefound campaign, follow below link:

1943: Race to Rabaul – Questions and Answers from Volko Ruhnke

– What is the historical background of the game 1943: Race to Rabaul?

By late 1942 in the Pacific War, the Allies had blunted the Japanese on the Kokoda Track and Guadalcanal. 1943 would see a broad Allied offensive – Operations such as CARTWHEEL, POSTERN, and CHERRYBLOSSOM. Under General MacArthur in New Guinea and Admiral Halsey in the Solomons, the Allies raced to conquer or neutralize the great Japanese bastion of Rabaul.

The Japanese would counterattack but never again overrun any substantial Allied position in the South Pacific. Indeed, they would struggle to reinforce and even feed their front line in the face of Allied strikes on Japanese convoys. But dug in, the Japanese exacted Allied casualties and held off the planned Allied reconquest of the Philippines until well into 1944.

– Where did the inspirations for this game came from?

As I researched my design Coast Watchers, I became fascinated by the severe logistical challenges that daunted the Japanese. The Allies conceived and effected a devastating counter-logistics strategy against their enemy: Allied air and sea power would seek to destroy waterborne Japanese reinforcement and supply of forward islands and coastal positions. With the maritime environment and undeveloped jungle of the New Guinea interior, shipping lanes were the key to victory.

Emblematic of the Allied counter-logistics success were the Japanese nickname for Guadalcanal – “Starvation Island” – and the destruction of several thousand experienced Japanese troops in the Allied air raids on a New Guinea-bound convoy in the Battle of the Bismarck Sea in early 1943.

The Japanese had to – and did – get creative in getting around the growing Allied air and sea control. They pressed destroyers, submarines, and amphibious barges into service as logistical life-lines to their front lines. The famous “Tokyo Express” is an example of creative Japanese use of warships as transports. A particular history of the Japanese Army in New Guinea written by Japanese veteran Kengoro Tanaka showed from the inside how tremendously challenging the logistical puzzle was for the commanders at Rabaul.

– Are there similarities with Phalanx’s “Race” series?

Oh yes! As the logo on the Race to Rabaul box art already shows, Phalanx is officially calling the whole series KEEP ‘EM ROLLING. (The painting is by Rafał Zalewski and the titling by Donal Hegarty.)

In 1944: Race to the Rhine and 1941: Race to Moscow, players represent Commanders who are racing with each other to advance in the face of an enemy who can at best hold ground and inflict losses. The speed of the intended advance in each case poses logistical challenges – how to move enough stuff forward fast enough – that become the main bottleneck constraining victory. The focus of play is supply: the provision, delivery, and consumption of fuel, ammo, and food, that wooden game bits represent physically on the map board.

I have played Phalanx’s Race games A LOT. When Jaro Andruszkiewicz proposed that I do a design with Phalanx, I knew very quickly that the game had to be “1943: Race to Rabaul” – and that my starting point for mechanical design would be the engine within Race to the Rhine and Race to Moscow.

So, at the heart of Race to Rabaul we have mechanics that fans of Phalanx’s Race games will find comfortably familiar:

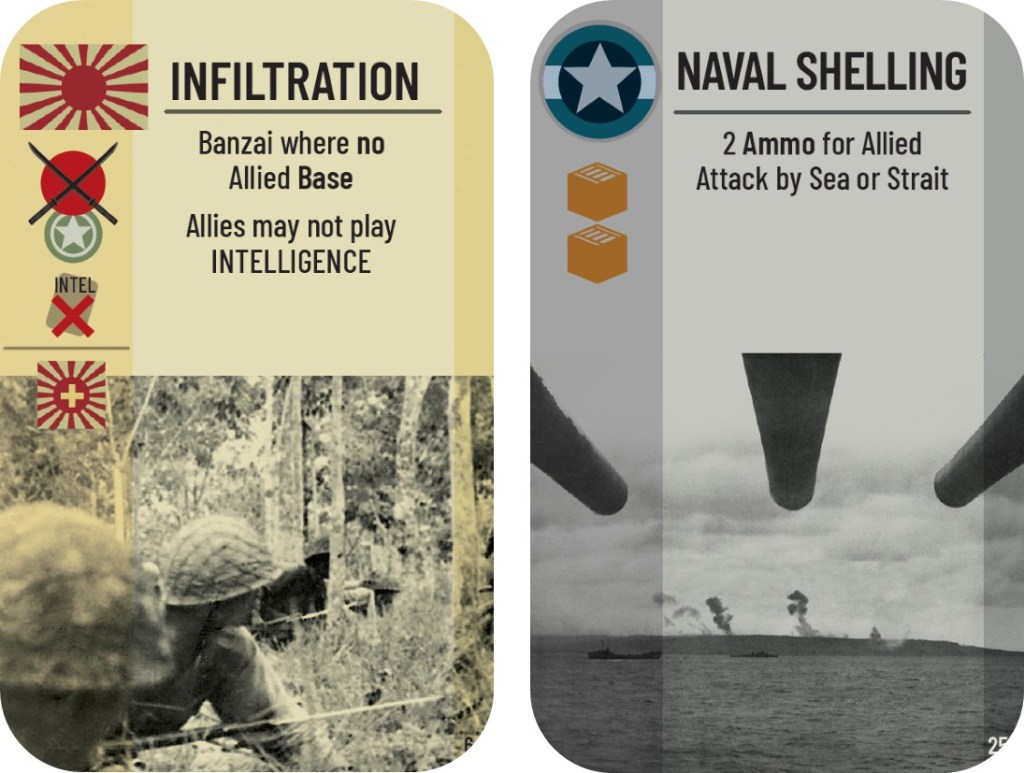

- Core and bonus actions, including Commander abilities and drawn cards.

- Ammo and Food bits.

- Unit display cards to hold them.

- Taking bits from a central stock to the players’ Supply Bases.

- Transport pieces, such as Japanese Barge pieces that work similarly to the trucks of Race to the Rhine.

- Air tokens.

- Combat determined by hidden cards and comparison of bits.

- Logistics steps to advance Logistics levels, consume Food, and reset reserves.

- And victory medals for taking enemy spaces and destroying enemy units.

– How did you feel about jumping into established system/design rather than starting yet another series?

It certainly helped things go faster! There was a clear target from the outset for what the game should deliver, and guideposts for how it could do so. Jumping in felt quite familiar to me, as my first couple published designs many years ago – Wilderness War and Labyrinth: The War on Terror – each rested heavily on other designers’ blockbusters – classic card-driven games of the 1990s and Twilight Struggle, respectively.

– Any influence of your previous designs (like COIN, Levy & Campaign or Coast Watchers)?

Certainly the COIN Series already had me well used to using wood bits to count assets, including troops. More interestingly, perhaps, Levy & Campaign let me experiment with articulated stock-and-flow supply models: that is, showing the amounts and locations of supplies (“Provender”) across a map. Levy & Campaign even included markers of transportation assets need to move the supplies (Carts, Mules, Sleds, Boats, or Ships). So you can imagine how I was immediately taken upon discovery of Phalanx’s Race games and thought that I could handle my own design project within that series.

Design of Coast Watchers, in turn, gave me the historical research in hand to model logistics in the South Pacific of 1943. In that game, to show how intelligence and security fought it out in an evolving regional military context, I needed to get a firm and detailed grasp of the offensive and counter-offensive campaigns. So I already knew the story of the Allied race to Rabaul in 1943 well.

– How different this theater is in comparison to other games in the “Race” series?

The particular historical campaign and setting for Rabaul meant that the design had to differ a good deal more from Rhine and Moscow than those two games do from one another. There are three substantial differences in the South Pacific of 1943 compared to Russia 1941 or France 1944 –

- We are racing not across French farmland or Russian steppes but along island chains and jungle coasts.

- The Japanese enemy impeding the Allied “race” is anything but on the run.

- Both sides – especially the Allies – must command not just logistics but counter-logistics.

– How did you adapt a general system designed for land campaigns into an amphibious operation in the Pacific? What decisions had to be made – what to keep, what to drop, and what to add?

The maritime environment for the Allied push to seize or encircle Rabaul means combined arms are essential. Players will handle shipping lanes, attacks across straits, convoys and other naval forces, airbases, and massed air support alongside land advance across near-roadless interior.

So, to take us to the South Pacific, I had to adjust the earlier “Race” model. Features in Race to Rabaul new to the series include:

- Different kinds of connections (“Routes”) between spaces: Land, Sea, Strait, and Coasts that are either land or sea .

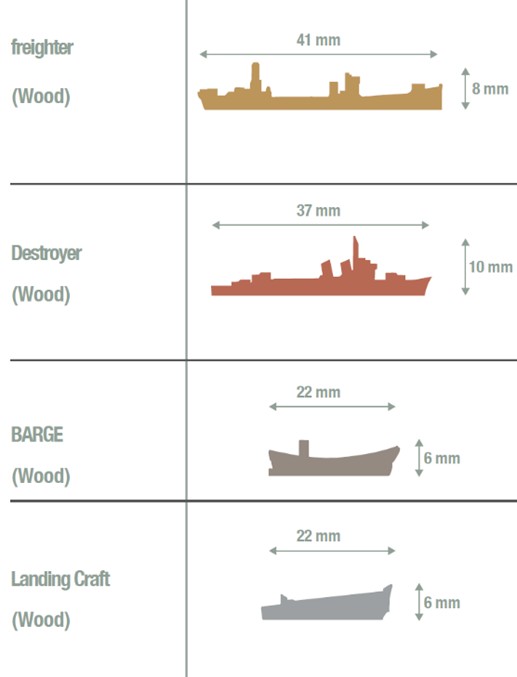

- Instead of trucks or trains, we use three types of Japanese Convoys plus Allied Landing Craft pieces.

- With almost all land movement by foot, we don’t need Fuel bits. Instead, we show transport of fighting units over water. Troops take the place of Fuel, and instead of just “Supplies” we have “Men and Materiel”. Ammo becomes useful in combat only if enough Troops are there to use it, while Troops without Ammo or Food are highly vulnerable to loss. Lack of Food removes individual Troop pieces. And Allied Attack over Land costs Food – representing not just rations but protection against malaria.

- We also get lot more Air support on both sides. The Allies must build new Airbases as they go forward, so that their Top Cover can protect their Shipping Lanes and their airstrikes can reach more Japanese Convoys.

- Finally, in the wide expanse of sea and impenetrable jungle, the Allies must first find the Japanese to strike them effectively. So Rabaul adds a new kind of Allied card: Intelligence.

– In the Pacific Theater we see Japanese not on the run, but rather executing active defense; how that is reflected in the game?

Imperial Japan’s troops are digging in to fight for every yard. Its naval forces are organizing to deliver reinforcements to the front lines. And its air forces can still reach out to strike Allied positions. To show the tenaciousness and creativity of the Japanese defense, we put that active Japanese defense in the hands of players opposing the Allied Commanders.

That calls for somewhat more involved, asymmetrical, 2-sided combat. The Allies can attack over Land or across Straits, can Invade by sea, Airdrop, and even bypass Japanese positions. The Japanese need to time “Banzai” counterattacks to wrongfoot the Allies and inflict Troop casualties. Success can force the withdrawal of exhausted Allied Divisions – diminishing the Allied ability to fight their way forward.

As in Rhine and Moscow, combat in Rabaul still compares numbers of bits on the map and on cards that determines the outcome of combat. But this time, the enemy is not just a random flip of a card but a human opponent. What cards in hand will they select to play or hold back? Are they bluffing?

Essential player decisions as well concern the locations and timing of Airbase building and Japanese fortification of their bases – both tied to intermittent Logistics Steps that reflect the pace of operations, largely in the hands of the Allied players.

The result (to the taste of some players but admittedly not all) is a true wargame rather than a “war euro”.

– While it might not be commonly known, one of the keys to the final Allied successes in the Pacific Theater was their counter-logistic strategy. Can you elaborate what that encompassed and how this is presented in Race to Rabaul?

Rather than going up against fully ready Japanese strongpoints, the Allies from late 1942 onward, sought to use their growing air and naval advantage to cut off, bomb, and starve Japanese garrisons. Then the Allies hit them once weakened – often from two directions at once.

In Race to Rabaul, the Allied Commanders can strike and Sink or Abort Japanese Convoys to prevent the delivery of Troops, Ammo, and Food to forward spaces. Allied Bombing and Land or Strait Attacks can reduce Japanese Men & Material before a full-scale Invasion or other Allied assault goes in.

Effective Japanese play will seek to slip more Men & Materiel through the Allied blockade. Japanese Commanders also can Bomb Allied Bases and Divisions. In particular, they will look to exploit any hitches in Allied resupply – striking enemy spearheads that might be inadequately resupplied after landing on a beach or assaulting a Japanese Fortified Base. Any Allied Troop losses in combat mean Medals for the Japanese.

– How many players will the game accommodate? How solitaire-friendly is it?

The rules in 1943:Race to Rabaul directly enable games with 2, 3, or 4 players. Each side – Japanese and Allied – has a pair of Commanders faced off against each other on one half of the map, with the ability of the 2 Commanders on a side to help (or perhaps sabotage!) each other. So that’s 4 Commander roles total, and 1 player can take each. But just a single player can take the roles of both Commanders on a side, so 2 players could face off as Japanese versus Allies. Or 3 players can play 2 Allies versus a single player as both Japanese Commanders, or the reverse.

Then there is an option for 2 players to play a smaller game on just half the map – New Guinea or the Solomons – between those 2 opposed Commanders.

Folks online have even suggested assigning each of 2 players the opposite side on each half of the map: one player takes the Allies in New Guinea and the Japanese in the Solomons. I had not thought of that nor tested it, but I think it would work!

For multi-handed play by a solo player, you would have to deal with certain hidden information: each Commander gets a hand of cards not known to other players. Which Bonus actions a Commander may do next and the resolution of Attacks relies on play of these unrevealed cards. So a single player would have to do their best to get around that hidden knowledge of card hands.

I did not design a solitaire system, so as not to slow down the project. I am not nearly as skilled at solo system design as others. My hope is that, if players like the game, that someone will design solitaire play for it – whether for Phalanx or as a home brew.

– What way will victory be determined in Race to Rabaul?

The first Commander to 12 medals wins. Like the other KEEP ‘EM ROLLING games, you earn medals to win mainly by capturing spaces and destroying enemy units. But, since only the Allies are taking enemy spaces in this race, the Japanese have a different key way to earn medals: by holding certain spaces representing the so-called “Bismarcks Barrier” for as many Logistics Steps as possible. The Allies, on the attack, set the campaign tempo and are the ones to trigger Logistics Steps to refresh their reserves, advance their Logistics Levels, and add fresh Divisions. But when they do so, the Japanese get a medal – until the Allies have broken the Bismarcks Barrier.

– As for the American players, leading MacArthur and Halsey, how could these two different theaters and theater commanders work together and how are they really separate?

As in Rhine and Moscow, Commanders on the same side each race up their own track. MacArthur (green) is conquering New Guinea, while Halsey (blue) fights up the Solomon Islands chain. The two tracks meet at Rabaul. But long before the Allies reach it, they can choose to help each other or to compete.

Bombing actions (for the Allies representing heavy bombers such as the B-17) can reach anywhere on the map, and Convoy Strikes (largely by medium bombers) within either Commander’s strike range. So you can help your partner by hitting the opposite track’s Japanese with your Air – and you would be advised to do so if that Japanese Commander is winning.

You can share Intelligence. So you can help your Allied partner by playing your Intelligence cards to enable your partner to Strike Convoys, hold off Banzai Attacks, and succeed in Allied Invasions.

And Allied actions typically determine when shared Logistics Steps occur – the timing of which can be even more critical than in the earlier games. Allied players will do well to coordinate when to trigger the next Logistics Step.

– Now, looking at Japanese side, how does this game present the famous interservice rivalry between Japanese Army and Navy?

Historically, Imperial Japanese Army and Navy forces fought together both in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. But New Guinea – with the larger land forces committed and key fighting in the mainland interior – was more the Army’s purview, while the Solomons fighting with major naval surface engagements was a region of greater Navy focus.

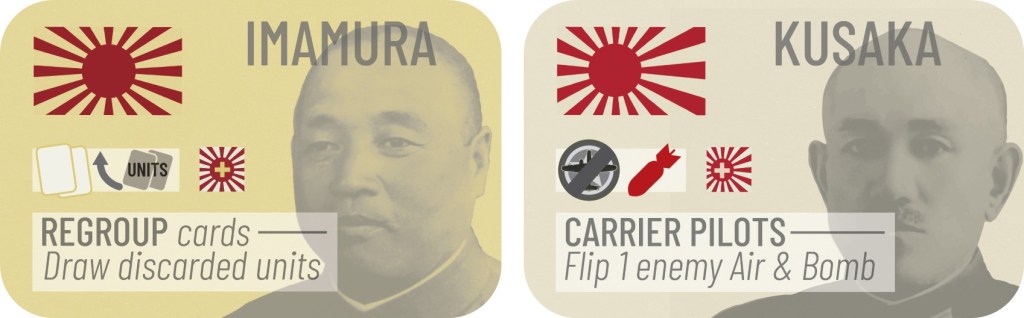

Rabaul portrays that divide by assigning New Guinea to IJA General Imamura (gold) and the Solomons to IJN Admiral Kusaka (white). The Commanders’ respective Bonus actions and the makeup of the Operations card decks of each reflect the historical tilts toward Army and Navy. The potential in play for 2 Japanese players to compete rather than cooperation then represents that interservice rivalry.

– This seems like a great Team vs Team game. What kind of information can be exchanged between players on the same side and which do they have to keep secret from each other?

The only hidden information in the game is what cards does each Commander hold. Players may privately show each other their cards. They may discuss what they will do, but only openly at the table.

– From a victory point of view, is it achieved by teams (so players share victory or defeat) or individuals? Are there any areas of cooperation within teams which could create tension or even friction?

Yes, beware! As the first individual Commander in the game to obtain 12 Medals wins, likely either MacArthur or Halsey will achieve that before the other – if neither Japanese player beats them to it. The same goes for Imamura versus Kusaka. If your partner is doing too well, you might not only hold back on help but even sabotage them!

For the Allies, a Logistics Step triggered when your partner’s forces are not really ready – have not had a chance to build a new Airbase to advance their Logistics Level or, worse, do not have enough Food positioned to feed their Troops – can upset the race. For the Japanese, both Men & Materiel and Convoys draw from the same limited pools. And any Men & Material arriving at the shared main Supply Base of Rabaul belong to both Commanders. So either can use timing of actions to rob the other. Commanders in a multi-player game will need to keep a sharp eye on their opponents on both sides!

– Will the game have one or several scenarios? How will replayability be ensured?

1943: Race to Rabaul includes 4 scenarios of varying length. Each starts at a different historical point in the campaign – the later the start point, the shorter the scenario. (So you can compare your progress in the longer scenarios to your historical counterparts over time.) The shortest scenario – CHERRYBLOSSOM – is also a simpler game to manage, as it is just 2 players on part of the map.

– When is this title supposed to be ready? How will it be funded?

The game design is finished – though we may always make some last-minute adjustment for scenario balance should we discover the need. Most of the art is done, but not yet the text-heavy items such as the rulebook and play aids.

The project is on preorder offer via Gamefound – with delivery of the game expected in the 4th quarter of 2026. I am posting sample materials and project updates to the games’ BoardgameGeek page.

Thank you for letting me spend so many words to present this background on the game!

Volko

I had no idea this was in the works – looks great! I’ll keep an eye out for it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

U just learned about this game recently and thought would be great to share more info about it!

LikeLiked by 1 person