To immediately jump to the Game Page follow the below link:

Michal: Hi Clint and welcome back to The Boardgames Chronicle blog. Really glad to meet you again! May I ask you, for those who do not know you, to tell the Readers about what you do for a living, what are your interests, hobbies and what games do you play? Also, what is your role in the design and publication of the Reformation: Fire and Faith?

Clint: I am a high school history teacher at a Catholic high school here in Australia. I’m married with kids and active in the local Catholic parish. So, wargame design is a part-time pursuit for me, as it is for most designers. I manage to cram in time in the evenings and weekends to work on my games. Although I’ve been playing board games and toying with board game design for about 20 years, I only got serious about it since 2020. I am especially inspired by Volko Ruhnke, David Thompson, Mark Herman, Cole Wehrle, Jamey Stegmaier and many others. My games tend to focus on high player interaction and interdependence, asymmetry, fast playtime, low downtime and lots of meaningful decisions for players.

I am the designer of Reformation: Fire and Faith. I came up with the idea and made a functional prototype. Game design is always a team effort though. I’ve had a lot of help from my co-designer Ed Farren in play-testing and graphics. Ed and I have collaborated before. He is very efficient and an excellent designer in his own right. The game is signed up with Neva Wargames, a relatively new Spanish publisher run by Jose Neva. I noticed Neva Wargames putting out some nice-looking games on historical themes and contacted Jose to see if he wanted a quick-playing game on the Reformation – he accepted! The game is currently with the P300 system on the Neva website, so we are waiting for 300 customers to register interest in the game by putting it on their Wishlist (no payment required).

Michal: Please tell us a bit more about what historical events inspired Reformation: Fire and Faith? And how your idea is connected to the great design of Here I Stand?

Clint: I am fascinated by the Reformation – both from a religious and a historical perspective. When I converted to Christianity about 10 years ago I had to choose which church to join, which forced me to read more on this time period, and read the arguments put forward by Protestant and Catholic apologists, then and now. I should state here that although I decided upon Catholicism, I hold no ill-feeling towards Protestantism and I understand the impetus behind it.

I was also drawn in by the fascinating geopolitics and tactical level military transformations of the time. The struggles between the French, Habsburgs, English, Ottomans, Venice, Scotland, Hungary, the Papacy and many other much smaller states were kaleidoscopic in their complexity but endlessly entertaining. To take one example of the political maneuvering of the time – the French lost the battle of Pavia to the Habsburgs, partially because 5000 of their Swiss mercenaries just left and went home to defend their own cantons from rampaging German Landsknechts. Losing Pavia meant that King Francis I was captured. This in turn meant the English sensed weakness and struck in north-eastern France.

Seeking allies against this double threat, the French turned to the one great power that might help them – the Islamic Ottoman Empire! This outraged the Habsburg Emperor Charles V, who had his hands full containing the spread of Protestantism in Germany. The Saxons, Hessians and Brandenburgers following Luther’s lead would be much better used to help defend Vienna from the Turks, but instead both the Pope and the Emperor found themselves facing a full-scale religious revolt at the same time as renewed Ottoman offensives in the Balkans and the Mediterranean. This was all taking place against the backdrop of a military revolution in which pike and shot, and artillery, were replacing feudal levies of armored knights.

The complexity of this time period, and the sensitivity of religion as a topic, has meant that few game designers have been willing to tackle it. The exception is “Here I Stand”, the classic 6 player card-driven game by Ed Beach. This game is a well-renowned and even genre-defining title that managed to cram tons of inter-faction dynamics and historical chrome into the CDG system invented by Mark Herman (who made the first such CDG – “We the People”). It is absolutely brilliant in so many ways. Baroque, intricate, full of theme. It is almost like a historical equivalent of Twilight Imperium – one of my other favorite games.

The problem? It takes way too long to play for most gamers. Ever since playing Here I Stand many years ago, I had kept the idea of a simplified version at the back of my mind. Then, when I started teaching religious history at a Catholic school, I found myself teaching the Reformation. A classroom game on the topic would sure come in handy. So, in 2024 I made one. The images below give an idea of this, including my very basic graphics made in PowerPoint and Word. In 2025 I revisited the idea and thought it might be worth making into a serious game, still using the basic concepts and inter-faction dynamics borrowed from “Here I Stand”.

Michal: What are the key components of the game? What factions does it depict?

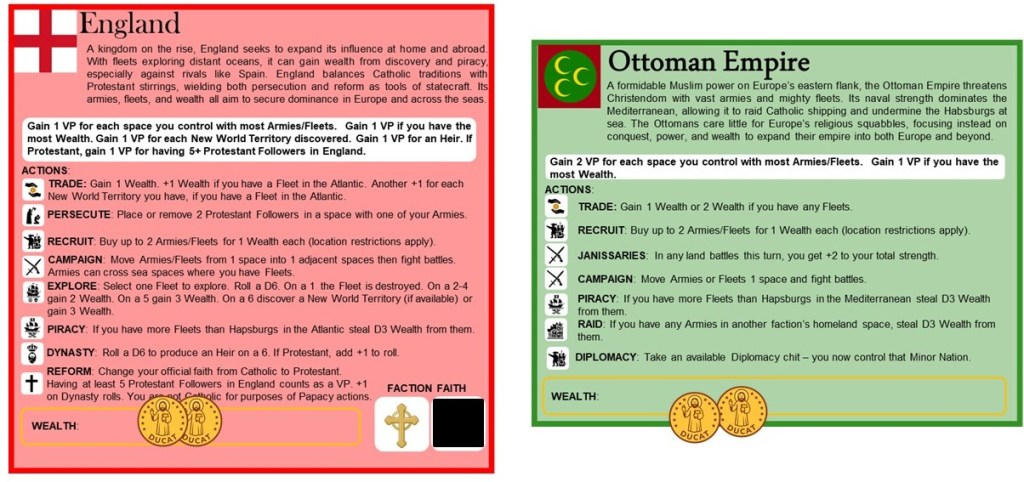

Clint: The components are very simple. A map, depicting a very simplified version of Europe in the 16th century with only 9 spaces: Spain, France, Italy, Germany, Austria, England, Ottoman Empire, Atlantic and Mediterranean. Then there is a counter sheet with units for all the factions, plus counters for Wealth, Knowledge, Minor Nations, New World Territories and a few other interesting little game features. Most importantly here are the player boards, which show you what you can do each turn. There are also player boards for the Bots, which you use in any game with less than 6 players (that includes solo play).

There are 6 factions in the game: Protestants, Papacy, Habsburgs, England, France and Ottoman Empire.

The Protestants and Papacy are religious-focused factions. They do have military forces, but they are relatively few in number and are not the main priority. The Protestants are trying to build up their knowledge of the Bible and translate it into vernacular languages, preach to the masses and debate the Catholics to spread their ideas. Their main goal is getting their Followers on the map. The Papacy is trying to contain the spread of Protestant Followers and remove them from the map as much as possible, plus place their own Churches. Both Churches and Followers are immobile and do not count as military units. But they can be attacked and persecuted off the map. I will go into more detail on how religion is handled later.

The other factions – the Habsburgs, England, France and the Ottomans – function more like the nations in a wargame. Amassing armies and fleets, fighting battles, aiming for control of spaces on the map. There are plenty of differences though. The English, French and Habsburgs have the option of Explore action – sending their Atlantic Fleets to explore the New World, gaining varying amounts of Wealth or a valuable New World colony (at the risk of losing the Fleet). This provides a great way for factions to gamble early on in the game in a high-stakes race for colonies. Two tweaks were made to the Explore action during the design process. First, my co-designer Ed Farren suggested that New World colonies should provide extra income during the Trade action if the owner has a Fleet in the Atlantic.

I loved this idea and implemented it immediately. I later thought that the Habsburgs should have a distinct advantage in exploring the New World, what with Hernan Cortez and Francisco Pizarro active during this time. I gave the Habsburgs a way to boost their Explore action with “Conquistadors” – effectively tripling their chance of finding a colony at the cost of an additional action. This means the Habsburgs will be raking in more money. But there are a lot of ways for the other factions to steal it! The English, French and Ottomans can all use the Piracy action to get that Spanish silver, and the Ottomans can also Raid on land if their Armies make it through to Austria.

The relationship between the military/political factions and the religious factions is also fascinating. I kept the Habsburgs as a staunchly Catholic faction – they can’t change their allegiance and will act as the strong right arm of the Holy See throughout the game. But England and France are a different story. England needed a historically-rooted incentive to convert to Protestantism, and this was solved in two ways. First, if England officially converts, they will earn 1 VP if England itself contains at least 5 Protestant Followers. This also gives 1 VP to the Protestant player, so there would be strong reasons for both players to work together in the conversion for England. I also wanted some of the high drama of Henry VIII and his wives without an entire sub-system and chart like Here I Stand. This became the “Dynasty” action – a simple die roll to gain a VP by producing a viable heir to the throne.

If England is Catholic, they need a 6 for this. But converting to Protestantism offers success on a 5 or a 6, as Henry can start divorcing his infertile wives. England can therefore grab 2 VP quite easily by ushering in the Anglican faith, which is handy because their opportunities for expansion on the continent are quite limited. France can also earn VP by converting to Protestantism and having at least 5 Protestant Followers in France. For both England and France, converting to the new faith costs an action – which Ed quite appropriately labelled “Reform”. This could be a wasted action if Protestantism doesn’t end up spreading in that nation or if the Dynasty action still fails. But it’s a live issue. Among experienced players, I expect that the Papacy player and the Protestant player will spend a lot of their table talk trying to convince England and France to side with them in religious terms.

Michal: Can you elaborate a little about game mechanics? How are you reflecting the depth of its inspiration, Here I Stand, with simplified set of rules, keeping the interesting gameplay?

Clint: The main inspiration from “Here I Stand” is the interaction between the two religious factions – the Protestants and the Papacy.

The Protestants are trying to convert people to their new faith (or rather, in their terms, restore an older and more purified form of the Christian religion). As such, their overriding focus is placing Followers on the map. As a rough approximation, each Follower piece represents 5-10% of the population converting to Protestantism. What the Protestant faction is aiming for is gaining a majority, or a near-majority, in the countries of Europe. So, their main way of earning Victory Points is by having 5 or more Followers in as many spaces as possible. Now, the Reformation did not initially take hold everywhere. Geographically it was concentrated in Germany above all, then England, then in scattered pockets throughout France. In the game this is basically where the Protestants will be focusing all of their efforts. They start with only 1 Follower on the map in Germany – this represents Martin Luther and the nascent reform movement that started to gather around him in 1517. From this humble beginning, I wanted the Protestants to build up and expand, sometimes rapidly, across the map.

To speed up their placement of Followers, the Protestants can translate the Bible into local languages – German, English and French. This is an idea I took directly from “Here I Stand” and of course from the actual history of the Reformation. Having the Bible in the vernacular language, and spread by the printing press, was key to the spread of Luther’s ideas. Bible translation is a simple, two-step process in the game. First you need to accumulate “Knowledge” through the Study action and then use the Translate action to place Knowledge markers on the three Bible language spots on the Protestant faction sheet. Initially, this was the only purpose of Knowledge. But then I expanded it to other uses – especially the Debate action, which is a competitive bid against the Papacy that can score 3 Followers at once. I liked the idea of carefully studying to build up knowledge in preparation for a debate – it’s a case of the game language matching the theme.

The Papacy works in a similar way to the Protestants – but in reverse. The Pope is trying to remove Protestant Followers, through Preach and Debate actions. Every 3 Protestant Followers is minus 1 Victory Point for the Papacy, so they are incentivized to contain the spread of the Reformation. The Papacy also has ways of building up their own points, through Churches. This general term refers to all the infrastructure of the Catholic religion – not just beautiful cathedrals (like St. Peter’s, which was being built during the Reformation) but also schools, Jesuit universities, seminaries, monasteries, trained clergymen and church councils. I was originally going to have a track or chart on the Papacy faction sheet to measure this but later decided to have it as pieces on the map – the Churches you see in the game.

This was because I wanted the Papacy to have some of physical presence on the map like the other factions. This was loosely inspired by the building tokens in games like Root or the resources placed on the map in Scythe. It has the advantage of opening up the Papacy’s primary victory metric to attacks from the other factions. Just like Protestant Follower pieces, papal Church pieces can be attacked and removed. This represents iconoclasm and persecution of Catholic clergy, as well as periodic waves of destruction like the Sack of Rome in 1527. Unlike Protestant Followers, I had the Papacy’s Churches cost Wealth. This Wealth is gained entirely through the Tithe action – which takes money from any nations that are still Catholic. Early in the game this includes three out of the six factions: Habsburgs, England and France. But England and France might convert to Protestantism, and a greedy Pope constantly demanding their money might hasten this on!

Michal: In what way the players determine victory? I would expect each faction will have slightly different path.

Clint: Yes indeed. Every faction can score Victory Points (VP) in multiple ways. The margins here are very tight – typically the wining faction will score 5 or 6 VP while second and third place will have 4-5. So a single point really matters. Every faction can score VP for control of spaces – this is hard to pull off as you need more Armies or Fleets in the space than all other factions combined. So, you might retain control of your own homeland, but taking control of another space is hard. Aside from control, each faction has other ways of getting VP:

The Protestants earn 1 VP for translating the Bible into all 3 languages (French, English and German), 1 VP for each space on the map with 5 or more Followers and 1 VP for having more Knowledge than the Papacy. So the Protestants need to focus on their religious actions – studying, translating and preaching.

The Papacy earns 1 VP for each Church they have on the map MINUS 1 for every 3 Protestant Followers on the map. They also earn 1 VP for having more Knowledge than the Protestants and 1 VP for having more Wealth than any other faction. So, the Pope also needs to focus more on his religious goals – but can also use the Tithe action to build up Wealth (for building Churches) and maybe get a point for rolling in cash.

The Habsburgs earn VP for each New World Territory they discover – and they are better at it than other factions because of their Conquistadors. They also earn VP for having 2 or more Churches in their homelands (Spain and Austria) and can earn VP for having the most Wealth.

The English earn VP for New World Territories and for having the most Wealth. They can also earn 1 VP for producing an Heir with their Dynasty action. The Dynasty action represents Henry VIII’s efforts to produce a legitimate male heir for his throne, and is easier if England becomes Protestant. England earns 1 VP if it converts to Protestantism and has 5 or more Protestant Followers in England. If it stays Catholic, it earns 1 VP for having 2 Churches in England.

France is basically like England but doesn’t have the Dynasty action. They will focus on military action, exploration and building up Wealth. If they stay Catholic they will want the Pope to build up Churches in France, if they go Protestant they earn VP for having 5+ Protestant Followers in France.

The Ottomans are the most straightforward – they can earn 1 VP for having the most Wealth but mostly they just get VP for control of spaces – they earn 2 per space instead of 1. They are an expansionist juggernaut and don’t care about the religious squabbles in Europe.

Michal: Do you plan – except for the main campaign – some additional scenarios? Or rather count on community to develop those?

Clint: At this stage, no. But I should point out that you can play with anywhere from 1 to 6 human players, and each player count will produce a slightly different experience due to the varying behavior of the bots. If the game is successful, I think it would be easy to make sequels, expansions or just different scenarios with print-and-play components to focus on two other phases in the European Wars of Religion: 1568-1618 and the Thirty Years War (1618 to 1648).

Michal: Now, as for Reformation: Fire and Faith itself, what makes this game unique?

Clint: A lot! This is the only game that lets you cram all the religious struggles and geopolitics of the 16th century into an hour, for 1 to 6 players. It is perfect for those who want the “Here I Stand” experience but are limited in time. The bot rules are innovative and simple. The main rules only take a few minutes to explain. There are also some similarities to the popular board game Root and to the COIN series – in that there are overlapping goals between asymmetric factions and multiple ways for players to hurt or help each other and dramatically change the game state with each turn.

I know that many people are also interested in religious themes, but there is a severe shortage of such games on the market. As I’ve said before, I believe that the whole “pike and shot” era is also going to make a major comeback soon, as people will want to move on from World War 2, World War1, Napoleonics and American Civil War. This game is a perfect introduction to both of these themes for new players.

Michal: To what extent does Reformation draw from your previous designs, especially One Hour WWII. I definitely see some similarities!

Clint: Yes, there are some strong similarities there. Both games have a heavy emphasis on player interaction and interdependence. You need to be talking to each other, looking at each other’s position, negotiating, etc. Both games have very low downtime, quick turns and near constant action – if you walk away for 5 minutes and come back you’ll see the game state has changed in ways directly relevant to your faction. Both games are also a kind of wargame-euro hybrid with an emphasis on efficiency and managing an action economy. You can’t just move every piece every turn. Finally, both games attempt to condense some incredibly large and complex wars into a manageable number of decision points for players – while still feeling like a wargame and not a complete abstraction. You’re still moving armies around on a geographically clear map.

One big point of difference is that the action economy in Reformation is much simpler – players simply choose two actions per turn, instead of choosing one action and then having other players interrupt the turn sequence to do responses. This was a tough decision, but the gain in simplicity is worth the slight loss of options for players.

Michal: How are you going to publish the game and where the players interested in the project can get more information or preorder it?

Clint: As already stated, the game is signed up with Neva Wargames. It is currently with the P300 system on the Neva website, so we are waiting for 300 customers to register interest in the game by putting it on their Wishlist (no payment required).

People interested in the game can create free Neva Wargames account and add the game to their Wishlist here:

Michal: Thank you very much for the interview! Any last word you would like to add?

Clint: The only thing I would add is that anyone who is interested in game design and history should follow me on X at @Clint_Davey1. I post regularly there and it’s a great way to keep up with the various games I’m working on.

Thanks!

Great interview! Been following Clint’s development and woolgathering posts over on X. I made a Neva acct and added the game to my wishlist.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I am very curious about this project.

LikeLike